It all started for me because I wanted to plant some apple trees. Just at the time I was mulling over what and how, we happened to visit my sister-in-law in Montreal. After dinner she pulled out a gorgeous skinny bottle and said “you must try this!” It was Neige, an ice cider from the original, premier producer in Southern Quebec, and it was freeking delicious. I looked at my better half across the table and said “yes we’ve got to try this!” Fateful words.

So, apples? Yes…but.

Concentrate? Left-over storage grocery apples? Fresh-harvested grocery apples? Organic apples? Bio-dynamic apples? Heirloom apple varieties? Bittersweet cider apple varieties? Abandoned or un-managed apple trees? Wild apples?

There are apple trees involved in every one of those options, but it’s an amazing range of options. At one end of the spectrum: low cost, predictable supply, juice consistency, low flavor. At the other end: scarcity, biennial-ism, high cost, variability of sugar/acid/tannin levels, more flavor (hopefully?).

There is much to be discussed about the economics and markets for growing apples. I’m not going to deal with that now, but here’s a quick view of what’s out there from the perspective of someone deciding what kind of cider to make. And if you are growing your own apples, you have to do the same comparison, and recognize that farming apples and manufacturing cider are two VERY different businesses, although in the same value chain.

China is the largest apple grower in the world, producing 37 million tons per year, 70% of which is Fuji. The US is the second largest producer at a mere 4 million tons, with 67% grown for the fresh market – Red Delicious, Gala and Granny Smith being the top three varieties. The top 5 apple growers in the U.S. are all in Washington state, with over 5,000 acres each. The labor costs associated with picking mean that the US is not an efficient producer of apple juice concentrate. Most apple concentrate used in hard cider production comes from Argentina, Italy, France, Turkey, or Poland. US orchards work mightily to make sure as high a % as possible of their crop makes the grade for sales to the grocery market, as that is where they can get the highest price. The other 33% goes to processing. Washington State has enormous bulk juice processing and cold storage facilities. You can buy tanker trucks full of bulk juice pressed out of cold storage pretty much all year round.

The largest two apple growers in Vermont are 400 and 300 acres, respectively. Then there’s my friend Steve Wood, who back in the late 1980s top-grafted trees in his family’s 60 (not a typo, not 600, 60) acre New Hampshire orchard over to British bittersweet and American heirloom varieties that had NO possibility of being sold to the grocery store market, with the crazy idea that they might be better suited for making specialty hard ciders. Finally, at the far extreme, Andy Brennan at Aaron Burr cidery in the Hudson Valley of NY, makes a cider from apples foraged from a couple of trees growing wild on Maine’s Isle Au Haut. OK those apples were “free”…all like 5 bushels of them, all like 500 miles away of them.

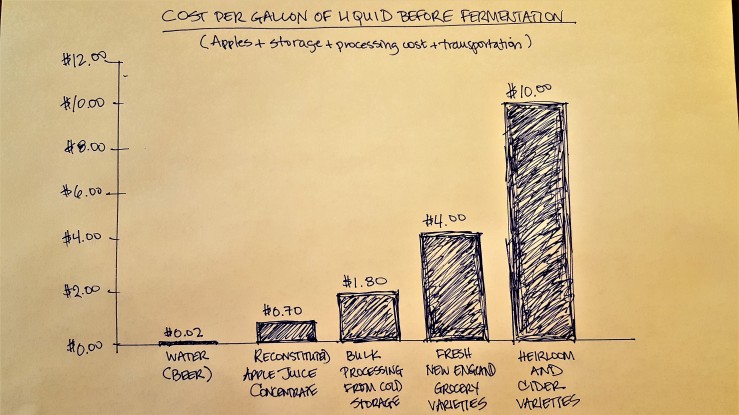

Buyers at stores and restaurants sometimes screw up the courage to ask me why the ciders in 750ml wine bottles are SO expensive. Here’s an approximate price comparison (vetted with other producers so a pretty good ballpark) for a gallon of liquid going into a tank to be fermented into cider –

– Frozen foreign concentrate, reconstituted with water = $0.70

– Bulk juice from left-over grocery apples, pressed out of cold storage = $1.80+

– Harvest-pressed grocery store apples in New England = $4.00+

– Heirloom and Cider variety apples, harvest-pressed at small scale = $10.00+

In the case of ice cider, we use our Vermont winter weather to do a natural concentration outdoors before fermentation during which we lose 80% of the volume of juice we started with. That increases the cost of the gallon of liquid going into the tank by a factor of 5 times.

And all of this begs the question “does it taste any better”? Hmmm, depends what the cider maker does with it, and who’s tasting.

The worst-case scenario is when you plant 1,000 trees of 42 different varieties on 3 acres in a biodynamic management program and hire someone 3 days per week during the season to do the work. That’s the route we chose of course. The $64 tomato has nothing on the $100 bushel of apples! While we wait for the trees to grow and start producing apples at their full potential (soon? I hope?), we purchase fresh apples – a mix of heirloom, cider, and grocery varieties – from 4 other regional orchards and press them, usually within 6 – 10 weeks of harvest. So we’re operating at the base cost of somewhere in between the two bars on the right hand side of the chart, MULTIPLIED BY 5.

It makes it especially rewarding when you are giving a tasting of ice cider at the farmer’s market and the elegant lady who’s been listening and nodding to your explanation finally takes a sip and says “That’s delicious! What grapes do you make this from?”

Great information, well presented. But your closing line left me wondering what typical costs, expressed in gallons, are for grapes. How do juice costs for traditional cider compare to wine?

LikeLike

Here in Oregon, Willamette Valley Pinot Noir grapes cost any where between $2,500 to $3,500 per ton. So roughly at the low end $1.25/lb.. Cider specific bittersweets and bittersharps can cost in the neighborhood of .35 to .60 cents per pound. Hope this helps answer your question.

Mark Zielinski

E.Z. Orchards

LikeLike