It’s been lovely hearing from those of you who have signed up to follow Cidernomics. A number of you have asked “So what scale IS sustainable?” There is no easy answer. That’s the whole project I’m on. This post gets at just some of the basics needed to start figuring it out. Meanwhile, keep the questions and comments coming!

Just up the road into Canada there is a medium sized producer of ice cider, run by an interesting woman who had succeeded in getting a contract to export to the Nicolas chain in France. All of a sudden she was building out more space and putting in some much larger tanks. We benefited from this because she was happy to part with 4 600L tanks and a 4-head gravity bottle-filler for less than $2,000. We didn’t own a truck, so my man was going to take the Toyota Highlander SUV and bring the stuff back in 2 or 3 trips.

Our biggest concern was coming back across the border. It’s not like you can hide a stainless steel tank under a coat in the back seat. We had no idea what kind of rigmarole we would need to go through – paperwork, exorbitant duty charges, official signatures, pledging of first-borns, etc. He eased up to the border guard in Lane 1 at the Port of Derby Line and rolled down the window. Yup, he was told to pull into the parking area and go inside the border station to see the customs officer on duty. Man, if this didn’t work our back up plan was pretty much unaffordable.

After waiting in line a mere 10 minutes or so, he got to the front and explained that he had two stainless steel wine tanks purchased second hand. The border guard asked what price we had paid, and proceeded to hand him a form. “Write a one sentence description here, put the value here, and sign it here.” he said, “That will be $10.75.” Done! Piece of cake! We really were going to try this ice cider thing after all. Three trips and three hours later, it was all in our basement. If we’d had a big enough vehicle, it would have only cost us $10.75 for the one trip. We were delighted to spend just $32.25.

Along with the tanks and the filler, we had purchased a small press and some plastic containers to freeze the juice outside for the ice cider process. We also needed a pump, small filter, hoses, some fittings, and some kind of corker, capsuler and labeler. These all fall under the category of “plant & equipment” in the broader category of “fixed assets”. Going back to the question at the end of the value chain post “Apples to Cider to You” – can I make money at $12.60 per bottle of ice cider FOB price? – knowing my fixed versus my variable costs is the key to the answer.

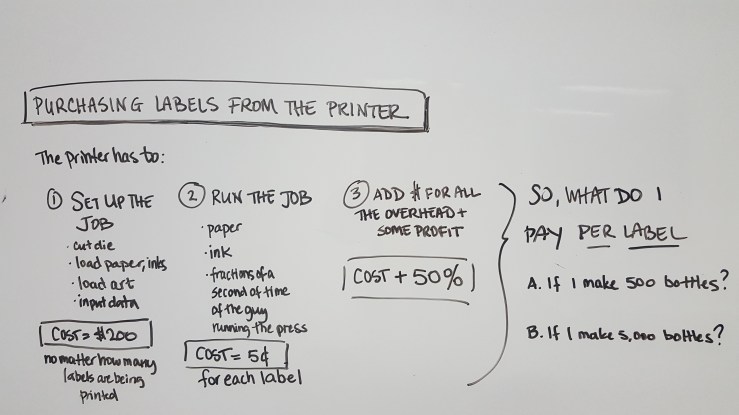

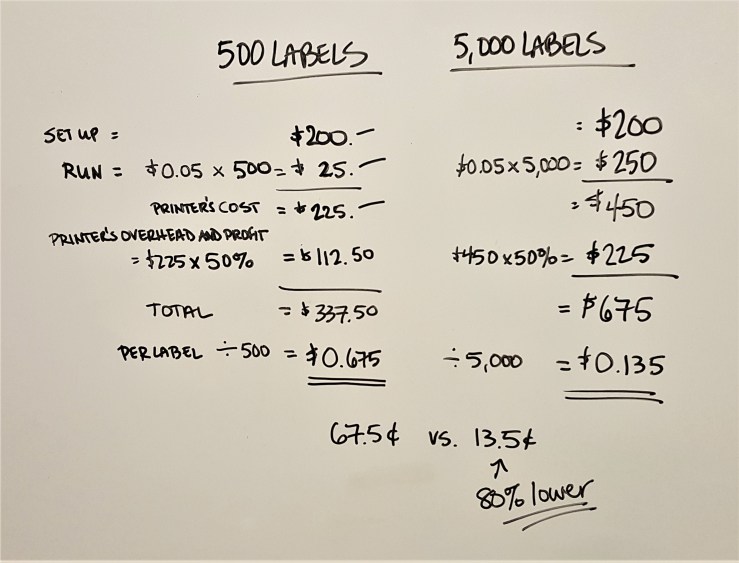

Variable production costs: apples and/or apple juice, production supplies (yeast, filter pads, etc.), bottles, corks, labels, capsules, cartons, and any hourly labor cost for pressing, bottling, labeling etc. Calculate these per bottle, and make sure to allow for some waste.

So, if my FOB price is $12.60 and my variable costs add up to $6.50, then the incremental money I’m going to bring in from each bottle I sell = $6.10. Also known as marginal contribution.

Fixed production costs: equipment, rent, utilities (mostly at our scale).

OK, so you don’t count the full cost of equipment in one year – that’s what depreciation is for. Most equipment is assumed to have a useful life of 7 years, so take 1/7 of the equipment cost as your annual fixed equipment charge. (We’ll talk about the difference between cash flow and profitability later.)

Overhead: Then you have all sorts of things that are typically considered “overhead” – sales, marketing, general, administrative expenses. For simplicity’s sake we’ll just call this all fixed cost. However, in future posts, I’m going to do a pretty deep dive on sales economics where we’ll parse that more finely.

The basic concept of break-even is the math that tells you how many bottles you have to sell at your marginal contribution rate to cover your fixed costs, after which the marginal contribution of each bottle goes toward your bottom line profit. In this example, if my total equipment purchases are $18,000, and I estimate that office, utilities, marketing and sales will cost me $5,000 per year, then I will need to sell (($18,000/7) + $5,000)/$6.10 = 1,241 bottles of ice cider, or just about 100 12-bottle cases, to break even.

You have to play around with this quite a bit, because 1) your variable costs per unit are different depending on the quantity you purchase, as we saw in the label example in “Economies of Scale, Cider Style“. And 2) fixed costs are really only fixed for a certain range. For example, you can make anywhere from 100 – 600 liters of cider in a 600 liter tank, after which you have to purchase a new tank.

The trick is to know where the ‘steps’ are in your fixed costs, and see if the volume at the steps will be sufficient to break even or better. In the diagram below, you want to be in situation B as you grow. Situation A is truly Breaking Bad. This picture is one of the key issues I worry about with small food/drink businesses!

My capacity at that point was 1600 liters (3 full tanks plus one to pump into, less some loss during fermentation). That’s 2,068 375ml bottles, and the variable costs of $6.50 per bottle are what I expected to pay to produce and bottle at that quantity. So theoretically, I could generate $6.10 of incremental profit on every bottle over 1,241: (2,068 – 1,241) x $6.10 = $5,044 of profit on a little over $26,000 in revenue. I would be paying myself a little over $1,000 in hourly wages as part of my variable production cost, and I could pay 5% interest on the $18,000 I invested in equipment, and take home another $4,000 or so for the year that it would take to produce and sell the ice cider. Sounds good, and might work as a secondary ‘hobby’ income, but it’s not going to support me at that level. So I’ll need to grow beyond that. (SO easy to say…)

If you are being smart, you spend a lot of time calling vendors and asking for quotes at different quantities and building a sophisticated spreadsheet that lets you model the picture of growth with some precision. (If you don’t know how to use Excel, find someone who does!) On the other hand if you are being romantic, what the hell. This is why they say that to make a small fortune in the wine – or cider – business it helps to start with a large one.