The timer on my computer rang out and I pushed myself back from the table and rose to go down to the basement and check on the progress of filtration. I was alone in the house for the week, trying to get the ice cider filtered and stabilized so we could leave it sit until we were ready to figure out bottling. The problem with making an alcoholic cider with so much residual sugar left in it is that the fermentation can restart. By that I mean that the yeast would come back to life, start eating the remaining sugar in the cider and turn it into alcohol, resulting in a completely out of balance drink. We were trying to arrest the fermentation by freezing the cider, hoping to kill the yeast. I would drag the containers of the ice cider outside where at least the weather was a cooperative -5F, all the murky yeasty stuff would settle to the bottom, then after a few days I’d bring it back in the basement, and then suddenly three days later it would be all murky again.I knew I needed to filter it, and so I got my hands on a little home brew vacuum filter apparatus. It came with three different grades of circular pads. One pad at a time, every drop of ice cider had to be filtered through each grade of pad. The little vacuum pump would create a vacuum in a thick-walled glass 3 gallon carboy with a heavy rubber plug, and the cider would be drawn out of the fermentation container, through the pad and into the carboy. The first stage was the toughest. In some cases it took an hour to filter 3 gallons. I had 120 gallons of ice cider that had to be filtered 3 times. I was avoiding doing the math so I wouldn’t feel too sorry for myself. 40 straight hours of filtration, not to mention all the time it took to stop and clean and replace the filter pad. Oh the romance of a cold basement, the soothing sound of the pump, the trickle of the cider falling brilliant and clear into the carboy. NOT.

While I waited for the next 3 gallons of cider to push though the filter, I went back to working on my estimates for how all the costs of producing and selling the cider would add up, and what kind of price I should be putting on a bottle of it. Well, that’s the way a lot of small producers would think about it as they got started. But it’s not necessarily the best or only way to look at it.

In fact, it was pretty easy to know what the price ought to be for one beautiful 375ml bottle of ice cider. I had only to look at the prices being charged by the Canadian ice cider producers right to my North. I also checked the prices of other sweet dessert wines – Ice Wines from Ontario, Sauternes, late-harvest wines, and my favorite name – Trockenbeerenauslese, the super sweet reisling from the Rhine Valley. Appropriately, ice cider is less expensive than those noble tipples. The midpoint of the Canadian ice wines was about C$27/bottle, or US$24. I expected to make something of similar quality, so asking a consumer to pay more than that seemed likely to increase barriers to sales, while asking less would just be leaving money on the table.

But could I make money at $24/bottle? To answer that question, I couldn’t just assume that a customer would come to the door or the farmers market and I would collect $24 in cash from her. I can’t just add up all my product costs and subtract that from $24. If I ever hoped to sell more than 100 cases of ice cider, I need to think about the whole process of getting the cider from apples all the way to the bottle at your table.

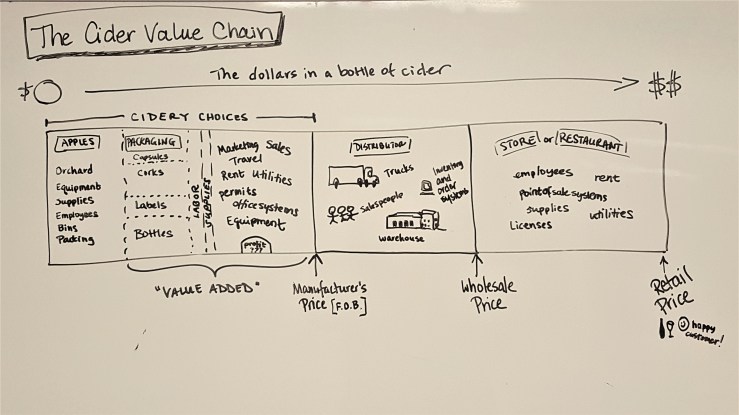

If I sell the bottle of ice cider to Willy at the local general store, then I have to charge the store something less than $24. The store has to pay rent, employees, insurance, supplies, utilities, advertising, and make some money. It turns out most stores need 25 – 50% of the retail price. Fortunately in Vermont, it’s typically closer to 25%. So that means I’ll get $18 when I sell it to Willy. But what if I want to sell it to my friend’s fancy restaurant in New York City? Then I have to sell it to a New York distributor, who will then sell it to the restaurant. The distributor has trucks, a warehouse, employees, order and inventory systems, and all those other expenses, plus he needs to make some money too. Typical wine distributors need to make somewhere between 26 – 35% of the wholesale price. At 30%, that means I will be selling it to a distributor for $12.60. From that I need to pay some part of my mortgage, utilities, insurance, my or some future employee’s labor…and looking backward, that set of costs and profit is also built into all the prices I pay for what goes into the finished cider – the grower from whom I buy the apples, the suppliers of winery equipment and supplies, the packaging producers, etc. This is what is meant by a’value chain‘: the whole chain of costs involved in every aspect of getting from the apple to cider, and from the cider to you.

Here’s my attempt at a visual rendering –

So, can I make money at $12.60 per bottle? More on that next time…

[…] is my feeble attempt at illustrating the concepts in my post “Apples to Cider to You“. I went back and added it into that post as well, but if you read it earlier, then this is […]

LikeLike